Phongsaly area.

Ban Seoropen, Ban Namma Noy, Ban Namma Gnai and Ban Houaygnoum villages. October 2007.

Pierre Evald

The field trip took place to the north of Phongsaly in the north eastern region of Laos up to the Chinese border from 17th to 21st of October 2007. Interviews, observation, photos and audio recording were carried out in the above mentioned villages. Ban Xoulin and Toung Kaolin yao villages and Ban La (Lu village) were passed through during the trek.

The survey’s main objective was to document the extent of preserved books and scrolls containing the migration story and religious taoist tradition among the yao in the remote villages of the border region.

The survey was fairly rewarding in terms of documentation and social observations but restricted by an obvious ignorance of the specific English terminology for religious practices on behalf of the guide, Mr. Senkeo. During the trip it became evident that the English language he had been taught didn’t include the capability to deal with matters in the spiritual sphere, but he was excellent in choosing the local yao guide, Mr. Tomkeo Saiyathad (61 years) from Ban Thung. Tomkeo was a well known figure in the villages visited and a great benefit for the whole trip: translating, socializing and supporting. When partying in the house of the local yao headmen in the evenings he also knew how to behave without going to excesses in drinking and smoking. Mr. Senkeo also is to be credited for his social skills in retrieving information from local yao informants and for his planning together with Tomkeo of the whole field trip and the sequence of villages to be visited.

During this field trip I realized that my trekking in the mountains now had come to an end at age 63. Senkeo had to carry my gear on top of his own as my ability to manage the uphill path could only succeed without any additional load to my bodyweight. Without his strength to lift this burden off my shoulders I could not have gone through the trek, the pounding of my heart was excessive as were the dots of light coming to my eyes. The realization that field surveying from now on belonged to the past was easily accepted and gratitude prevailed in memory of many rare and outstanding moments in the mountains of southern China and elsewhere. So many dreams have materialized in these remote corners and fortunately field notes have been preserved to keep me occupied for years after retirement in 2008.

Yao villages in northern Laos were following the general pattern in agriculture and relocated repeatedly due to exploitation of the land. The state’s policy with its governmental assimilation practice of forced settlements and access to school socialization and public health care were being carried out, and no cross bordering in relocation of villages was reported.

All interviews started with a brief introduction to tell the yao people gathered, mostly in the evenings, about the interests and objectives for the field study. All communication had to go through Senkeo, from English to Chinese, to Tomkeo who again translated from Chinese to Yao dialect. And the respond had to pass through this chain to reach back to the interviewer. It is obvious that misunderstandings and uncertainties could easily pop up considering also Senkeo’s before mentioned insufficient vocabulary. To compensate partly on this deficiency all interviews were following a structure with five specific questions only and follow-up questions were rarely possible:

Age of the interviewee (all males). Stayed in the same village?

Is there a shigong or daogong (taoist priest) in the village?

Is there any books in the village? (King Ping’s Charter: Ping Huang Quandie.

Or: Register for crossing the mountains: Guo Shan Bang).

Has he seen any paintings of the taoist pantheon?

Has he known any taoist wooden temples in this village or in other villages?

Day 1. October 17th.

By local bus from Phongsaly to Ban Muang Ou Tai up north, with Lao cassette music in abundance. In the evening Senkeo was looking for a

local yao guide to join us. First Tomkeo was not at home, a second possibility with a too authoritarian attitude was ruled out and luckily

Tomkeo returned late in the evening and agreed to set off with us the following morning for the three day trek to the hills up to the border to

China. Nam Ou River, a contributory joining Mekong a short distance to the north of Luang Prabang, is passing through Ou Tai. Returning

from Phongsaly after the trek was by riverboat from Hat Sa with several stops in local Lao villages down the Nam Ou to Luang Prabang.

Day 2. October 18th.

Hilly trekking in frictional terrain also following and crisscrossing a river Nam La-Chai for more than 20 times finally reaching the far Ban

Seropen near Chinese border in the afternoon after passing through Ban Namma Gnai and Ban Houaygnoum. Those villages were to be

visited later on and tonight’s stay was in Ban Seropen. A one hour stay for lunch was at Ban La, a Lu village, like when returning on day 4.

In Ban Seropen Lanten Yao are residing. Lanten Yao are called ‘Indigo Yao’ in Chinese. Same as Lao Huay, ‘Lao of the Streams’,

an identification given to them by the Lao Government after 1975. Other names for this subgroup of yao are Lu Mun and Mun Yao.

It was told in the evening that yao people came to Laos from Guangdong and Guanxi 300 years ago.

45 families are living in 37 houses making a total of 256 people.

Shigong/daogong present in the evening gathering with around 20 yao males. Very relaxed atmosphere and obvious interest in the

coloured photos of yao paraphernalia being passed around.

Interviewee:

Age 55. Male. Shigong/daogong. Also school teacher and member of a management team of four men in charge of village matters.

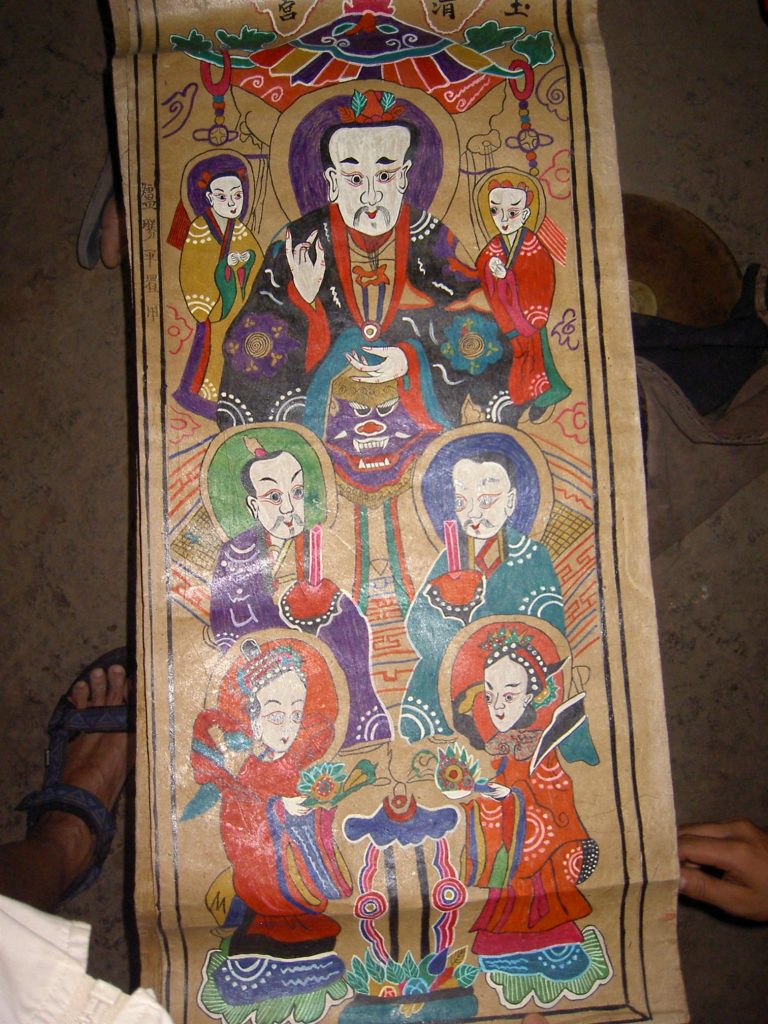

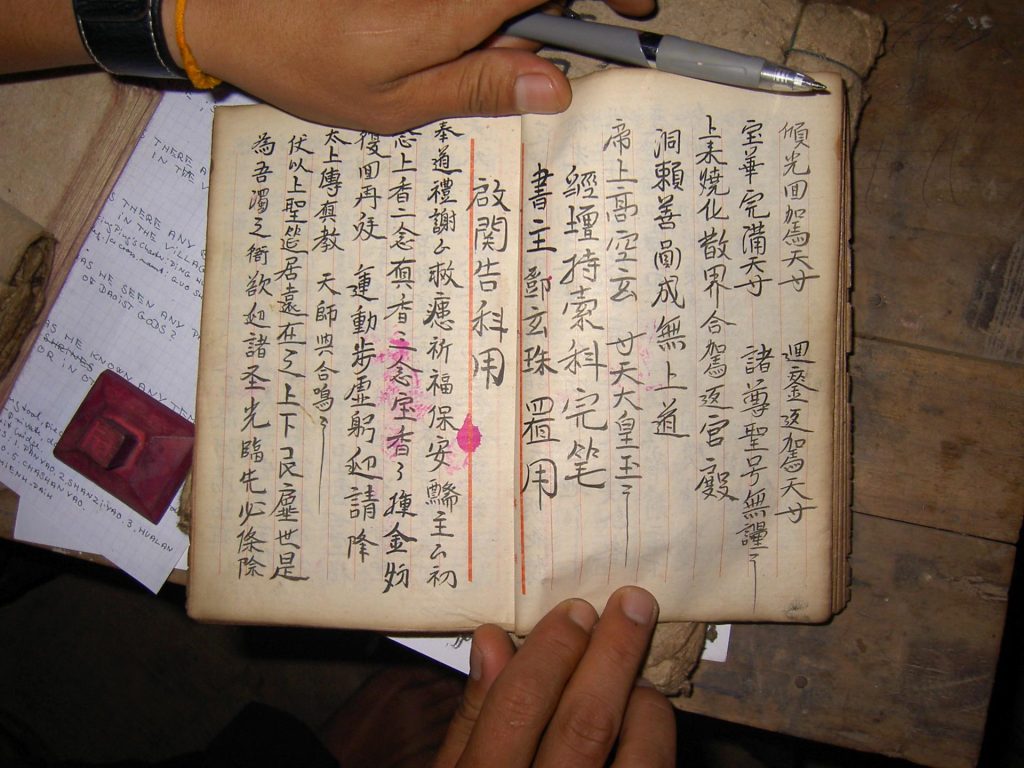

Books were kept in this house of the headman and used for rituals on a daily basis. Paintings have also been seen in this village.

Temple buildings have not been seen. In houses local altars (mienh-paih) to be taken outside for ceremonies where also paintings were shown.

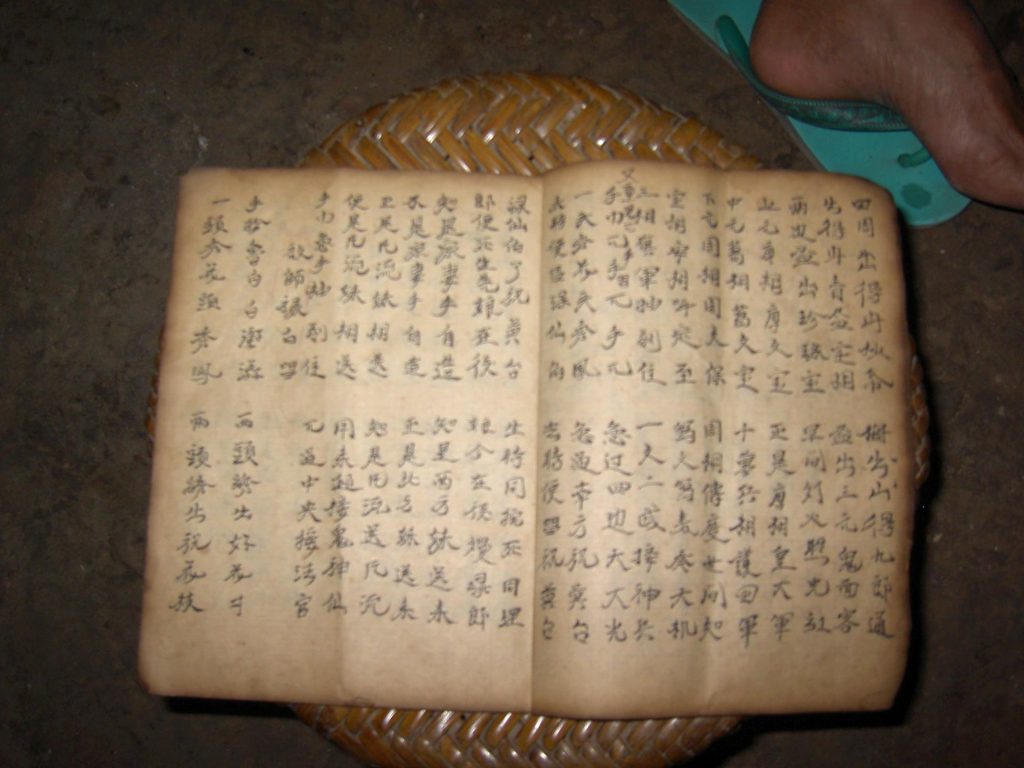

Books brought from other houses:

Yao history book.

Yao birth day book of boy Calada.

Yao history book of rituals for weddings.

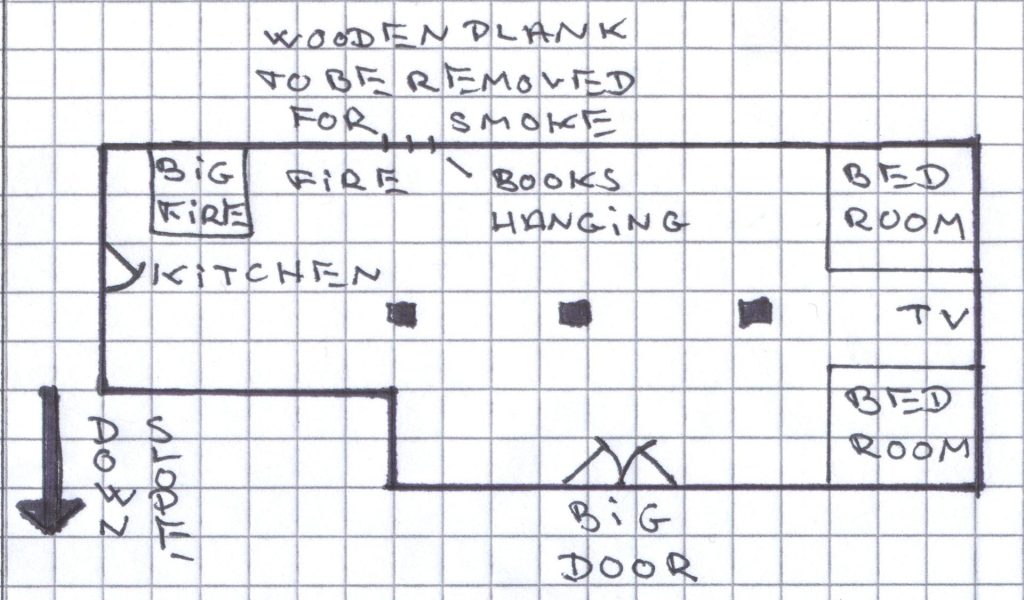

Plan of house interior:

A double door to the south can be locked, other openings give access to pigs and chicken running free in the house.

Also photos of other paraphernalia in the headman’s possession.

Nine festivals on a yearly basis: Yao New Year, Small New Year, February New Year, Langfun Festival, Burning of Lights,

Festival for sacrificing of animals, Farming Festival, Food Festival and New Rice Festival.

Name giving 3 days after birth (nouang). Special food for the mother consisting of chicken and eggs. A ritual involving a

chicken is performed to check if a boy is healthy and well.

A normal dowry consist of 30-80 silver coins, two pigs and many chickens, including those to be eaten at the celebration.

At the funeral the body of the diseased is washed, black paper provided in the coffin and a chicken blood offering is performed.

Next to the headman’s house sounds from a mentally disturbed women could be heard.

Asking Senkeo where it was appropriate for me to go for defecation, his answer was, ‘Anywhere’. Accordingly any stools when

delivered were immediately being eaten way by the numerous pigs walking around and following defecating persons.

Morning photos of village before short trek to Ban Namma Noy.

Day 3. October 19th.

Trek to Ban Namma Noy and staying overnight in Ban Namma Gnai.

Lunch at Ban Namma Noy. Lanten Yao. 48 families in 34 houses making a total of 231 people.

Interviewee:

Age 74 years. Male. Staying in same village all his life.

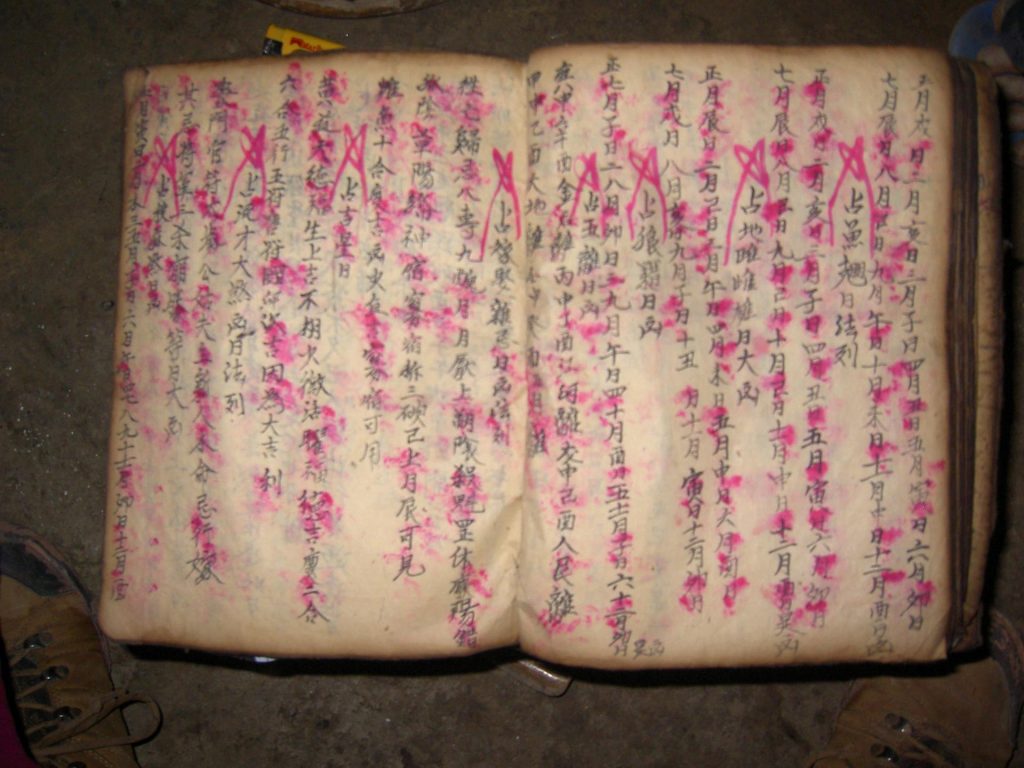

Books:

- Phumsavadan. The Mind and History of Yao minority. Big size.

- Hopvanh. Horoscope calender for wedding.

- An abbreviated edition of the headman’s Phumsavadan (1) to be copied by other persons in the village.

A basket full of books is shown, and also a statue of Pan Hu and a ritual sceptre, both made of wood.

Two taoist paintings are with headman. Painter is from Ban Phangsan Gnai to the north near the border to China; same painter and recognizable style as yesterday evening in Ban Seropen.

A wooden taoist temple is remembered from the village’s former location from where it moved seven years ago. Music instruments, cymbal and drum, from the temple ceremonies in the former village are still in use and kept with the headman.

In the next house a local altar (mienh-paih) where the fronts were not to be totally opened for photo. Pan Wang was mentioned in this context.

In the afternoon onward trek to Ban Namma Gnai to stay overnight.

Yao Lanten. 54 families, 40 houses and a total population of 258. 120 are women. Their origin is in China.

Two interviewees:

Age 71. Male. Shigong (called Taigong). Curing sickness.

Age 46. Male. Daogong. Performing funerals.

Books kept in headman’s house:

- KhaoThaohou. On medicine. Small.

- Daogong book.

- Yao prayer book.

- Lapleng. Astrology and omens.

- Calender. Single piece of paper.

4 and 5 are kept in daogong’s house and used by daogong in their practice and rituals, including weddings. Dowry is usually pork and some chickens. At child birth name giving follows after 3 days; pork and chicken are given to Shigong. If the baby dies the calendar (5) is used to settle the day for funeral which takes three days. The body of the diseased can remain in the house no longer than 21 days. 3 chickens and a pig to the Shigong for the funeral ritual. Ban Namma Gnai and Ban Houaygnoum were the only two villages visited who had a daogong.

Taoist paintings are kept in a box only to be taken out for use during festivals. The painter is from Ban Phangsan Gnai village near Chinese border; same painter as reported in the other villages.

A small wooden temple, 40 years old, is remembered to have existed in the village’s former location; relocated to this place 15 years ago.

From the daogong’s house was brought his belongings: Cymbals and a drum; some embroidery, a sceptre and a tooth.

Recorded music. Two takes with drum and two different cymbals played by daogong, age 46. Recording also with his narrative.

The tooth was told to originate from a mammal called a deal: Black, like a monkey, said to be living in SE-Asia and China. Other sources name it muaij, Malayan bear (Helarctos manayanus), which is to be found from Assam to Indochina, Malaysia and north to Sichuan in China. In other yao villages also a corner tooth from this animal was to be seen, with a small bell of bronze and a Chinese coin as its tongue, fastened with a string to tie around scrolls with paintings. In Muang Khua I was told that this rare mammal was without toes but had long fingers, walking on the ground and not in trees. Its tooth was said to signify power. It eats people in the night after having been playing with their bodies during daytime. Taller than man, like a bear, takes buffalos also.

House of the headman where we stayed overnight is a pile dwelling with open ground floor and an entrance door from the staircase and door to the first floor balcony. House is oriented east-west, with kitchen in the east end of the house.

In the evening dinner party with food and lots of drinking for more than 15 male guests in the headman’s house. 2-3 chickens were slaughtered in the kitchen end of the house. Daogong, age 46, expressed his compliment for the interest in yao culture and I responded on the importance of keeping alive the rich tradition of the yao in a changing society with its governmental assimilation policy. The art of not being governed by the state is still crucial for the yao as well as other minorities in the border mountains.

Day 4. October 20th.

From Ban Namma Gnai to Ban Namma Noy and further on to Ban Houaygnoum and Ou Tai. Arriving Houaygnoum at 11 a.m. for lunch and brief interviews.

The village has been in this location for the past four years from a location to the north of Nam La-Chai river (old location still on map). In the beginning they moved from Hum Yum village in China.

2 interviewees:

Male. 61 years. Male. 57 years.

Shigong (sickness, death, offering of chicken) and daogong (dealing with spirits when people dies).

Books brought from other house:

- Horoscope for marriage.

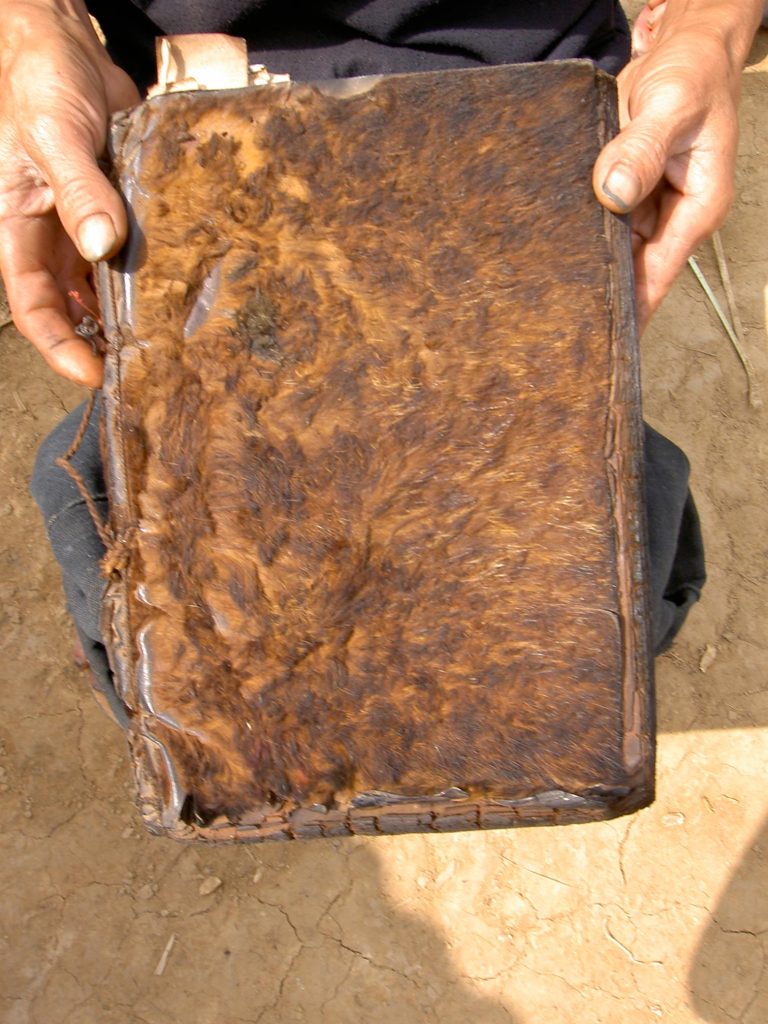

- Lapleng. Astrology calendar, including traditions and customs. Binding with fur from wild cat.

Paintings are kept in the village.

Inconsistent information: In general the yao came to Laos 300 years ago from China. A temple is recalled in the former village Hum Yum in China. The age of the temple is said to be around 100 years. The population of this village came from China four generations ago and this small temple for taoist gods is remembered in China, to the north of the present location of the village. No temples are remembered in Laos.

Preliminary observations:

- No wooden temples seem to exist in this part of NE Laos

- Several informants remember wooden temples in earlier locations of the village in Laos

- Wooden taoist temples are mentioned still to exist in China

- No scrolls with text were seen anywhere. Book formats only. Used as manuals for the performance of rituals

- Shigongs and daogongs with their ritual duties are integral parts of the religious culture in yao villages

Day 5. October 21st.

With local bus from Ou Tai to Phongsaly.

Yao ceremonial robes.

Seen in Vientiane 14.11.2007 at Lao Ethnic Handicraft Centre, opposite Thalat Sao market. Four robes, all with elaborate embroidery and ornamentation on back side: Hexagrams, Taoist figures, dragons and Chinese characters.

Rev. by Pierre Evald 02-05-13